- Home

- Tammy Letherer

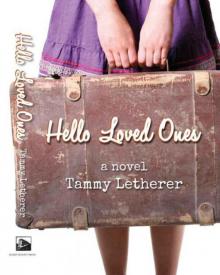

Hello Loved Ones

Hello Loved Ones Read online

Hello Loved Ones

a novel

Tammy Letherer

Rapid Transit Press

Chicago, IL

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Song lyrics by the fictional group The Raptures taken from “Three Good Reasons”

by Chicago folk band Sons of the Never Wrong. www.sons.com

Copyright © 2012 Tammy Letherer

All rights reserved.

www.TammyLetherer.com

ISBN-13: 978-1466459397

ISBN-10: 1466459395

Book Design by Eat Paint Studio

www.eatpaintstudio.com

To my family...

Those who came before,

for they are the roots,

And my children,

Lincoln, Boone and Genevieve,

the most beautiful of leaves.

“Facts are the barren branches

on which we hang the dear,

obscuring foliage of our dreams.”

—Natalie Babbitt

Sally

Sally Van Sloeten has a father, same as anyone. Just because a mother or a sister calls a person a deadbeat doesn’t make it so. Because a brother says trust me, you’re better off doesn’t mean he knows the first thing about anything. So when the Father-Daughter banquet comes along like a long-awaited signal from above, is she supposed to curl up with her ratty afghan, re-read the latest issue of Seventeen magazine and snivel poor me, guess I’ll miss out? Damned if she’ll be lumped in with this crowd of worshipers who lay their desires at the Lord’s feet, then call it a day. Whew! It’s in God’s hands now.

“The gospel of John calls us to worship in spirit and in truth,” said Pastor Voss, and all around Sally his flock began nodding like pigeons, flapping their bulletins against the August heat. The pastor breathed in deeply and added, with a touch of drama, “Also, of course, with joy.”

Sally made another mark on her bulletin under the word JOY. That made 43 times he’d said it. She wished he’d just shut up! It was so damn hot. The air in the sanctuary was thicker than the potato-cabbage casserole they were having for Sunday dinner. Sticky thighs were glued to worn-out pews. Swollen feet were mashed into sensible pumps. And the smell! Sally detected lilac perfume and cow manure, and each time the pastor opened his mouth it was like a sprinkle of stinky cheese. Didn’t he know, didn’t God know, that she was bursting to be set free? The letter stuck in the waistband of her skirt had to be put in the mailbox today or her father would never get it in time. By now it must be soggy with sweat. She felt it clinging to her back, and it was starting to itch.

“Turn with me to the second book of Acts, verses forty-six and forty-seven,” Pastor Voss said, and while parchment pages gently rustled, Sally clenched her teeth. She’d spent every Sunday of her life sitting in the same pew at the Holland Dutch Reformed Church beside her mother Prudy, her sister Nell, and those bony, slumping, ski-slope shoulders attached to her brother Lenny. She’d long since counted every pane of stained glass, every beige ceiling tile, every flame-shaped bulb in the dusty wrought-iron chandeliers overhead. If it weren’t for the Father-Daughter banquet and the fact that she was finally old enough to go, she’d have run clean out of diversions.

Everyone would be there. Not just girls from the church, but most of her classmates from Holland High, and even some from Holland Christian High School. For lots of them it was the first time they could wear high heels and make up. Sure, they’d have to suffer through Pastor Voss’ lecture on how young ladies should respect themselves as God’s unique gift, and look for nice young men who would do the same, but that was a small cross to bear considering they got to dance to real music. Not the good stuff, of course, like The Beatles, but maybe a little Donovan, or something from The Lettermen. Romantic, grown-up music. And none of it would be special if she had to take her Uncle Ollie. Her sister Nell went with him three years earlier and she said he had muck on his shoes, didn’t use a napkin, and refused to dance to “Ah, Sweet Mystery of Life.”

For Sally, there was no mystery. The banquet would be the beginning of life the way it was meant to be. That was why she wrote the letter.

Dear Dad,

I know you don’t remember me too well, but I’m sixteen now and this is the year I get to go to the Father-Daughter banquet at the church. It’s an event of major portions! All the girls in town will be there. It’s Saturday the 18th. Please write soon and say you’ll come.

And then, because she felt strongly about this, she signed it love, Sally. Because, more than anything, she wanted her dad to know that she wasn’t like the rest of them. She didn’t hate him. She remembered the red sweater he used to wear, the way he once tickled her and threw her in the air. How his hair shone, black and stiff like a beetle’s shell. The overcoat that smelled like cold air. He got bored with them, is all, with nothing more exciting to look forward to than the annual church bazaar, with its stale poppy seed muffins, pipe-cleaner refrigerator magnets, Jesus Christ nightlights and plastic rain caps that folded up to look like little purses. He probably couldn’t understand why his wife had gone from a pretty girl who liked to laugh to a woman with a grim flat mouth who shared more of herself with the Lord than with anyone else. He simply couldn’t bear spending half his life sitting in a church pew listening to Pastor Voss yammer on. He was exactly like Sally.

To think he’d soon hold a piece of her! Her very heart, and yes, her sweat and tears as well. Would he smile and think back to her as a little girl, wearing pink ruffly rubber pants, shouting daddy, daddy! whenever she saw his car drive up? Maybe he’d be sad, thinking of all the years he’d missed with her. Maybe he lived with memories of her every day and once he held that letter in his hand, it would be too much to bear and a sob would escape him. Sally saw him clutching his chest with one hand while he held the letter to his lips with the other.

Or… Here the picture rewound itself and he was holding the letter in his hand, a frown crossing his grizzled, beaten face. He balled the paper up and threw it into an overflowing trash barrel next to his front door. He spit on it for good measure and went stumbling back inside, pulling a moth-eaten brown robe tighter around his frail, stooped frame. He sat on the one chair he owned, lit a cigarette in the dark, and wished he had moved even farther away. He cursed and vowed to chew out the mailman if he ever delivered letters like that again.

Sally heard the word JOY again and made a harsh mark on her tally. Rejoice! read the cover of the bulletin. You are part of the family of God. Bullshit. Was God going to teach her to bait a hook, or bowl a strike, or measure the hypotenuse of a triangle? Was God going to meet her boyfriends, if she ever had any? Would he walk her down the aisle, this very aisle with its dirt-red nubby carpet? She’d have to rely on her brother Lenny or Uncle Ollie and the most beautiful day of her life would be ruined. And what about her future children? They wouldn’t have a grandfather.

Wasn’t Sally just as deserving as the next girl? She looked across the congregation. There was Martha Malden sitting beside her father, who looked kindly and safe in a blue striped tie, the same Mr. Malden who had stood beside her in his undershirt when she spent the night with Martha back in seventh grade. He had helped them make pancakes, telling them to add a smidge of water to the batter. Sally had never heard the word smidge. For ten minutes he stood with them, testing the batter with his finger, again and again, and when it was just right the three of them cheered like they had saved someone’s life. Sally remembered feeling stunned that a grown man would take so much time to help his daughter accomplish someth

ing so minor. Then there was Debbie Rinkema who always sat in the back pew. Her father ran the supermarket and once while Sally was standing in the canned vegetable aisle she heard him on the phone in his office saying “I love you Deb-Deb” before he hung up. Imagine saying those words for no reason at all! It was as if he’d said I’ll bring home some milk. Those were the things she was missing, those little acts of fatherly kindness that, if she’d received them, might have made her a better person. And if she were a better person she might not dream of walking into the banquet on her father’s arm, with girls like Martha and Debbie staring, saying so that’s her dad!

She had to get to the mailbox! If God could really see into her heart, he must know that she regretted, just a little, calling her upstairs neighbor Miss Snootie-Patootie. It was an honest assessment, for sure. But she shouldn’t have said it out loud, in front of her. Being grounded for a week was completely jeopardizing her plan. Here she sat, squirming, feeling like a mouse stuck in a sticky trap (or was it a rat?) when there came a sneeze, followed by the sound of a marble hitting the wooden floor. Christ! It was Mr. Van Adder’s glass eye, again. There was a rustle through the congregation as the eyeball rolled between the pews. Mr. Van Adder was allergic to dust motes and three varieties of grass, and it was the third time in two weeks he’d sneezed his eye out. Hallelujah for a high pollen count! It was a small distraction, but she’d use it. As she started to slide toward the aisle, the rolling stopped. Mr. Dekker had the eyeball under the toe of his shoe, and Mr. Van Adder held up his hand in a gesture that said he’d retrieve it after the service. Pastor Voss abruptly launched into announcements.

“I’d like to wish Lenny Van Sloeten a happy birthday,” he said. “Lenny is 18 today.”

Sally was startled. She thought the pastor didn’t like the Van Sloetens much. When he looked out over the congregation he never seemed to see them. When he called the heavy-hearted forward to pray with him at the altar and Sally was dragged up by her mother to kneel at his feet, he never touched her bowed head the way he touched the others. The Van Sloetens were poor, and their tithes didn’t amount to much. Sally supposed Pastor Voss was obligated to turn his attention to those who paid for it. Maybe she was wrong.

“For those of you who haven’t heard, Lenny will be working here at the church as custodian,” Pastor Voss said.

Sally leaned around Nell to look at Lenny. He was tracing a vein in his forearm, flexing his fist to make it stand out. He acted like he hadn’t heard the pastor and maybe he hadn’t. Lenny had been deaf in one ear since he fell out of Uncle Ollie’s hayloft when he was six years old.

Pastor Voss cleared his throat. “I’m so pleased to be getting Lenny’s help. He’s a fine young man, and...” He trailed off, as if searching for something more to say about him. “He’ll be taking the furnished room downstairs so... Well, he’ll be here 24 hours a day. To look after things, you might say.”

What sorts of things needed looking after in their small church? That was the question on every face. It didn’t matter. Everyone knew the truth. It was Lenny that needed looking after. First it was a few nights out late. Then a handful of cut classes, one or two bad grades, and a graduation ceremony that Lenny pretended to forget. Finally two weeks ago he was arrested for fighting out behind Louis Padnos’ scrap metal yard. He broke Cash DeVries’s nose, which was the size and color of a crook-neck squash to begin with and now looked like a watermelon split wide open, all red and pulpy with black seed-like stitches. Pastor Voss bailed Lenny out with money from the church offering plate on condition that Lenny move into the church and work it off. Of course everyone knew. At the Wednesday night prayer meeting Pastor Voss asked the Lord to be a guiding light for those struggling with hostilities and tempted toward unruliness, and Lenny’s face turned nearly as stiff and red as the brand new hymnal books.

“Let’s all keep Lenny in our thoughts as he begins his service to the Lord,” the pastor said. “As you know, there are many forms of worship, and mopping floors is one of them.”

Everyone in the first three rows swung their necks around to stare. Mr. Van Adder’s good eye fell squarely on them. Tiny Mrs. Byer, barely four feet tall, craned so strenuously from her seat in the front pew that Sally saw her shiny blue hair peek into the aisle at knee-level, as if it were a fluffy bag on someone’s lap. And the look the pastor gave them smacked of smugness. Sally watched him pull out a starchy white handkerchief and wipe his shiny brow. Before returning it to his pocket he examined it, the same way she examined a tissue after attacking a blemish on her face. Like he expected to see blood. She imagined that it would please him to bleed for the sake of his flock, just like it pleased him to hold Lenny up as an example.

Not that it mattered. Lenny’s birthday was ruined a long time ago, seeing as it was the same day their dad walked out. Supposedly Lenny, only eight years old, started swinging a bat at him. Sally doesn’t remember that night, but what seems obvious to her is that Lenny was a hothead even then, and hasn’t gotten any better. He deserved to be humiliated by Pastor Voss. But with that accomplished, couldn’t the pastor please move on? She couldn’t exactly get up and walk out while he was talking about her family.

“Shit,” she whispered under her breath, wiggling back and forth. She looked sideways at her mother to be sure she wasn’t heard. She couldn’t afford any more punishments. Once she mailed the letter, she could breathe a little easier. She could even allow herself to savor today’s more immediate joy, yes, JOY. Lenny was moving out! The circumstances were not ideal, but she didn’t care. Once Lenny was gone, she was getting his bedroom. No more sharing with her sister, the two of them pressed into the same sagging bed, Nell’s thick legs trapping Sally to the wall. No more tripping over Nell’s open books that populated every inch of the floor like little tee-pees. No more suffering under Nell’s critical eye while Sally experimented with mascara and lip liner. No more discussions about the plight of African pygmies or other topics Sally cared nothing about. No more Miss Goody Two-Shoes, that was Nell.

She waited a few moments, then let out a loud cough.

“Choking!” she whispered to her mother. “I need a drink.”

Her mother put a hand on Sally’s arm and glared at her but Sally ignored her and continued coughing as she pushed her way out of the pew and hurried down the aisle. Freedom! Soon the service would be over, but for now there was no one in the foyer, so she bolted out the front door. If she was stopped, she’d say she felt faint and needed air. Anyone who remembered the time Mr. Veldeer fainted from the choir risers last summer would believe her. (And who could forget, the way his head bounced off the floor with a hollow thwack?)

She sprinted down the sidewalk and flung herself at the mailbox on the corner. Taking the letter from her waistband, she saw that the ink was fine but the seal had come unstuck. She licked it quickly and pressed the flap down with her thumb. It popped back open. Now what? There was a gas station across the street. Surely they’d have some tape. But she couldn’t go there. Cash DeVries worked there. Imagine seeing that mangled mess of a nose up close. What would she say? Hey, sorry my brother broke your nose. Can I have a piece of tape?

There was a good chance he wouldn’t know who she was. He was a year older, and went to a different school. He played baseball, like Lenny, and she’d seen him at some of the games, but never spoken to him.

She heard the first notes of the organ drift out the sanctuary window, which meant the sermon was over and the last hymns were starting. She hesitated. She could always wait until Wednesday to mail the letter, when her punishment was up. It was only a few days away.

No. She’d come this far. Cash probably wasn’t even working today. Anyway, it wasn’t like she was the one who hit him. She had nothing to do with it.

She put the letter back in the envelope and glanced once more at the church before sprinting across the street to the gas station. If she didn’t hurry she’d never make it back before the Doxology.

Bursting through

the door, she nearly collided with a pair of work boots sticking out above the counter. Attached to these was a slouchy kid sprawled half off a beat-up office chair. He had long hair pulled into a ponytail and bad skin. And a red swollen nose with black stitches down the middle. Whoa! Lenny did that? Sally didn’t know why, but the whole incident seemed a little funny at first. Lenny always talked a big game. He hit his dad with a bat when he was only eight, blah, blah, blah. And the way he still carried that same bat around with him everywhere he went was pretty strange, but she never thought he was dangerous. He was just her brother. Now, face to face with his handiwork, she felt afraid for him. This was serious.

Cash looked up lazily and raised one eyebrow.

“Got any tape?” Sally said, panting. She flicked her eyes over him quickly and then stared out the window. She had to act too distracted to look at him. Otherwise how could she avoid seeing that nose?

“What for?” he asked. He showed no sign of knowing who she was.

“I need to borrow a piece.” Another glance in the general direction of his chest. The label on his coveralls said Larry.

“I suppose I could scrounge some up.” He didn’t move.

This was ridiculous. She had to look at him. She sighed and put her elbows on the counter. Ouch. There it was.

“That looks painful,” she said.

He transferred a wad of gum slowly from one cheek to the other. “It ain’t too bad.”

She couldn’t help herself. “How’d it happen?”

He shrugged. “Got in a fight. You oughta see the other guy, though.”

Sally blinked, considering for a split second that this might be a guy named Larry who happened to work at the same gas station as Cash, and happened to have a broken nose. Then she remembered she was dealing with a teenage boy. Someone like Lenny.

Hello Loved Ones

Hello Loved Ones